Texture of Space-Time – Yasufumi Takahashi’s brane world

By Kazuhiro Yamamoto

He took out a pile of shirts and began throwing them, one by one, before us, shirts of sheer linen and thick silk and fine flannel, which lost their folds as they fell and covered the table in many-colored disarray.

from: The Great Gatsby

Scott Fitzgerald

Introduction

Yasufumi Takahashi’s sculptures are idiosyncratic. Idiosyncratic can imply either abstractness or concreteness in a common way and it also implies belonging to a category different from three-dimensional works that offer contrasts with their flat surfaces in a general sense. Furthermore, it is also different from tactile works with regard to works of sculpture as indicated in classic aesthetics.

Takahashi’s sculptures are idiosyncratic in that they are different from sculptures from the past century and typify the 21st century by targeting both space and time. This fact may be applicable to other sculptures considered to be important these days as well, and not limited solely to Takahashi’s works. In this sense, his sculptures visually explore the issues of entity and time/space in ways that are similar to the principles of phenomenology and modern physics, both of which are major methods of grasping world knowledge born in the early part of the previous century.

1. General Sculpture Theory

There is almost no common form in Takahashi’s works. His works do not converge with any specific forms or shapes, some being oblong, some being towering and some being cubic. This suggests that there is no consistency in external form. It suggests also that the invisible internal form may be more important than external form for this sculptor.

Although there is no consistency in his forms, a certain rule applies with regard to creating such forms. This rule concerns the method of the piling, or stacking, of materials. But unlike the stacking method used in minimal art, Takahashi creates such forms by depositing particular materials. In his case, the material is cloth. As he emphasizes, whether cloth is used or not remains unknown to the “viewer”. Some fabrics are woven and some are knitted. Takahashi’s works include piles of apparel piled tightly together. In effect, while the form of his work is sculpture, his utilization of fabric-like elements remains unclear and poses some pertinent questions among “viewers” with regard to his choice of materials. (We might also include his “mass and void” 1989-90 within this genealogy, a work which shows equally illustrates the surface “skin” and layers of growth rings of a Norway spruce.)

On the other hand, steel frames sometimes support these fabric-like materials. What is the role of these frames? They are likely to have no formative meaning. They simply support the weight and quantity of piled cloth. Generally speaking, the forms created by these materials seem to be relatively unimportant to this sculptor’s works. What is it, then, that he is showing us if it is neither the material quality nor form? The answer will be found in how the accumulated material appears. It must be a manifestation of accumulated materials.

For those of us viewing his works, he probably does not require that we bother to consider the initial appearance of the form. Or if there is general sculpture theory, it may require that we assign these primary elements to a parenthetical position as we pass through the outward

forms and pour all of our concentration into the appearance of the material. In this regard, the popular apprehension of sculpture (form and color) may not apply to Takahashi’s works.

In his existing works, most of his fabrics seem to come from clothes. His works after his stay in New York in 2004 can clearly be seen heading into the interior of this apparel. Or perhaps, they are heading into the internal form of the human body.

When we view Takahashi’s works, we are required to maintain a perspective that is in a different dimension from the well-toned muscles of the subjects that we can see in the works of Michelangelo or Brancusi’s highly abstracted forms.

2. Special Sculpture Theory

His use of cardboard as his material and the human body as his form in his latest work “Time Layer” fits in comfortably with our lives. However, the unreasonable differences between the forms of general human body sculptures and those in Takahashi’s sculptures clearly show that Takahashi’s sculptures are not at all mere human body sculptures

using cardboard. Human bodies are not re-created nor are they portrayed. Things that appear to be human bodies are only sought out as a single quintessence of his “Matrix of Space”. Still, human bodies are used here because they are the most familiar figures to us as “viewers”. The same

could be said about tree-like plants and animals. Perhaps the best visual factor for overcoming this subject/object dualism is to use the the form of the human body, which is both the central part of our identity as the “viewers” and, at the same time, the objective consitutent of “what is being

viewed”. At this point, we are required to abandon our view of sculpture which has been considered to be a given fundamental since the times of ancient Greece civilization and is still being proliferated even today.

In phenomenological terms, while epoché(parenthesizing)is a requirement, this is a “work”, not something that is required by the sculptor himself; it is a necessary requirement of the work itself, or of “what is being viewed”. The aforementioned “unreasonable differences” make the

request. When considered in comparison with “Athena” or Rodin’s “Dying Slave” and other works, there is no lapse in the fatuity of Takahashi’s sculpture entitled “Time Layer”. But as we “viewers” eye this work through our own bodies and a “disparing sense of discomfort”, a consciousness with

regard to “what is being viewed” leads our intuition towards an awareness that these works have been done in the same gauge. These disconforting human bodies which have had their superficial skin removed show that the “viewers (us)” and “what is being viewed (sculptures)” do not confront

each other but rather by giving us a look indicate that both we and the sculptures are one in the same.

On the other hand, the characteristic features of cardboard as a material are utilized in various ways. First, when viewing the work directly from the front, you can see a human body formed from cardboard with light being transmitted from the other side. At the moment you notice the light through the sculpture, as the “viewer”, you too change into “what is

being viewed”. At that same moment the sculpture is no longer a threedimensional figure as it now appears more like a silhouette keeping out the light and, at the same time, like a medium that allows some light to penetrate. We exist as a “shadows of the sculpture” there. Or, we could say

the sculpture, as “our shadow”, becomes an icon between the light and us. In this way, the entities of “light – sculpture – us” encounter each other in an equal relationship within the inter-space dualism of the “viewer” and “what is being viewed” that dissolves in this moment. Imagine an eclipse. Of

course, the minimized quantity of the sculpture differs from those of the massive earth or moon. And it is capable of unifying us, as the “viewers”, and the sculpture, as “what is being viewed”, as if it were photons passing airily, like a neutrons, through all of the materials. The sculpture stops being physical body at one point and is given a form of its own within our consciousness.

Aside from this kind of eclipse situation, the sculptures reappear in front of “viewer” as visual physical masses. They will appear as “unreasonable differences” whether they are viewed as original bodies in their entirety or as bodies reduced by the scraping off and discarding of skin. This is why the artist himself calls sculptures a medium rather than object.

However, sculptures as medium give too much freedom to the viewers for establishing the ecliptic situation as mentioned above. On the other hand, at the “Matrix of Space” exhibition at the Utsunomiya Museum of Art in 2004, the limitless perspectives offered to us, as “viewers”, differs from the single perspectives found in the more condensed concept of photographic images. (Illustration 1)

Illustration 1: Yasufumi Takahashi’s 2004 painting, “Matrix of Space”

Let us consider the term “Layer” that is also a part of the title. “Layer” is literally “layer”. The “layer” is the most important concept in Takahashi’s sculpting journey. “Strata”, another term for “layer”, was used as the title for Takahashi’s sculptures in the last century. However, there seems to be bigger difference between “strata” and “layer”. The difference is not merely lexical. As “Strata-the Tree-“ produced in 1997 shows, “strata” creates such situation in which a deposition of a certain event makes only the top layer visible. For example, the upper layer and the lower layer of social stratification in social science are assumed to be equal. Just as individuals within a social system prefer that their vectors constantly move upwards among the strata within a society, this tends to give those in the upper layers more power. In one of Takahashi’s works titled “Strata” the upper layer, or surface layer, is dominant when it comes to creating form.

The lower layer remains invisible.

On the other hand, “Layer” is different from his previous works since the artist himself has employed a temporal axis within the spatial layer. Since “Strata” is impermeable, by making the internal parts of the work impermeable, “Layer” has permeability, and by making the work’s surface and the superficial skin permeable, the work has acquired a construction that directs our glances towards the internal parts of this work. While the overall impression of “Strata” is one of deposits and hardening that make any exchange of layers difficult, “Layer” has unfixed

exchangeable layers that do not interfere with each other due to their permeability. (Illustration 2)

Illustration 2: Our world and other branes, referred to hereinafter

Surprisingly, the indications are that, since the end of the 20th century, Takahashi’s sculptures have been executed in the same way as his two-dimensional arts (screen image, photograph, painting, graphics etc). The excellent two-dimensional arts that we now find today within “a single frame” seem as though they are layered in infinitely raised powers (Xn). (Xn) All the layers being permeable make the inside layers visible. This holds even within the deeper layers as well. This fact shows that twodimensional surface graphic content is layer-stacked from the shallowest layer to the infinitely deep layers and at the same time are able to achieve hyper-dimensioning making them appear as being two-dimensional. Just imagine movement on the screen of a movie or TV program when you think of paintings or pictures with permeable layers.

Takahashi works, when seen in the same light, by achieving a permeability of the superficial skin on the surface of the sculpture, the relationship between the ”viewer” and ”thing being viewed” is not an A / non-A type of disconnected relationship but rather it is converted into a series of A, A’, A’’, A’’’, A’’’’, A’’’’’ consecutive relationships.

Because of this, many of the 2oth century artists tend to speculate about the dualistic concepts of borders, or boundaries, between the relative categories of the self and the world in their sculpture, leading to a situation in many ways similar to the disintegration of an atomic nucleus. In this situation, borders become permeable. In Takahashi’s words, superficial skin is transformed to the “amniotic membrane”. In

contemporary words, Takahashi introduced “brane” (the membrane, or ?

-brane found in string theory in theoretical physics), something similar to a membrane, which separates two things but is connected by its permeability, into sculptures. Brane is invisible. If you want to visualize it, you might

consider a pastry similar to mille crepes. (Illustration 3)

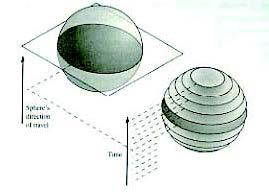

Illustration 3: The branes of a sliced cube over time become a cube

What is the meaning of the title “Time Layer”? In physics, “time” means straight lines connecting a certain point of time to a certain point of time and are one- dimensional, similar to other one- dimensional relationships such as up-and-down, right-and-left and back-and-forth. As I mentioned before, graphical content arts have already achieved temporal dimensions “in a single frame” by introducing permeable layers.

In order to go further into the essence of Takahashi’s sculptures, we shouldn’t rely solely on our eyes; we should invoke our wisdom and recall the invisible world. Let us reconsider the concept of “unreasonable differences”. The differences between our familiarity with our own human bodies and/or body sculptures and Takahashi’s sculpture forms are more than simply visual differences, (this is a variant of visual form) and it must be understood that the form of the achievement of a sense of discomfort is not the form that we see directly before our eyes.

If we invoke the familiar bodies and forms of ourselves and those of our family in the history of sculpture, the form before us is both a past or future form. What has been removed is not spatial form but time itself. This is important not because Takahashi’s written text explains it in words but because it is perceived by the viewers as a time lag. This fact is not instinctually accepted. More likely, it is produced through intellectual conduct such as certain kinds of soul-searching and contemplation. The instinctually perceived discomfort is also a lag between the moment of intuition and the moment of realization after reflection. The differences between the naturally recalled familiar human body forms and variants of visual forms that we see before us finally come to fruition only when it is understood that such differences are the results of forms having undergone increases

and/or decreases from certain prototypes. Such increases and decreases are not in increments of time but of space.

If we invoke that method not as artists who invoke phenomenology, a rigorously scientific field of study, for execution but as solely the “viewers”, we have to be loyal to the basic phenomenology of Edmund Husserl rather than the applied phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty. For example, when viewing visual arts, one is not permitted to invoke any knowledge about Ernst Haeckel’s ontogeny process – the process in which the “form” of protozoa and fish appearing while fertilized eggs repeat cell division as they pass through the various steps from fertilization to the birth of a human being – nor the phylogeny process – the change of form animals follow in the course of evolution from protozoa to fish to reptilians.

(Illustration 4)

Illustration 4: Ernst Haeckel’s “The Genesis of Foetal Mammalia”, 1874

That is because viewing visual arts has nothing to do with any disparity in the amount of knowledge of the viewer and knowledge must be put into parentheses and accepted by under conditions of innocence with no distinctions. In this way, we can discover not the form in the womb but changes in the form after birth in the visual discomfort of Takahashi’s sculptures. What we can imagine simultaneously through our eyes and minds is not an analogy between ontogeny and phylogeny but rather the changes in form of an individual in his passage from birth to death. It is as if we are seeing a succession of many screen images in a single frame right in front of our eyes.

4. Texture of Space-Time

Although the concept of layer stacking is in agreement with the previous concepts, after his stay in New York in 2004 Takahashi’s works have undergone certain changes in ways that attract the eyes of the “viewers”. While sculptures have the advantage of inviting glances freely from all directions, they also possess a dilemma in not being able to offer only a single, crucial point of view. These changes seem to happen in order to overcome this dilemma. Sculptures used to be merely objects to view and be viewed with a traditional sculpture mindset, but they are now visualizations of knowledge. This is probably due to the integration of the above developments and the certainty of the age of the screen image. For example, Brancusi took pictures of his sculptures in order to offer only one point of view. This tended to fix the light of a sculpture’s most sparkling moment in time. Still, sculptures are sculptures.

We could say that Takahashi has also found a certain way to visualize sculptures to base “what is being viewed” on some absolute concept. However, this was done in a totally different dimension from Brancusi, who literally established his three-dimensional sculptures into two-dimensional pictures. By diminishing one dimension, sculptures settled into screen images. But, Takahashi tried to visualize what is so hard to establish in order to bring about a single point of view with regard to the three-dimensions of up-and-down, back-and-forth and right-and-left, with the addition of the forth dimension of time. That is a way to continuously induce the best perspective for viewing sculptures with only a single point of view by matching changing light sources with the sculptures themselves. By regulating the light that may fall on the surface of a sculpture, the artist is not providing a fixed single image that might pass as a photograph. One inevitable way to derive a direct line (one-dimensional) “light?sculpture?”viewer” relationship from the viewer’s perspective is by transmitting light into the interior of the sculpture, without the utilization of visual equipment (photographs, cameras, etc.),

While “Woman” and “Man”, relief plaster works exhibited after his stay in New York, offered actual images, by treating his sculpture as superficial skin that seemed to have been dissected from the body and by diminishing one dimension, Takahashi has tried to present actual images in “Time Layer” without altering any of the four dimensions. The most important factor here is that the actual image is not one membrane but layered membranes. This is not meant to imply that time is layered. Rather it implies that “what is being viewed” becomes an image and that the image is layered. Consequently, we can say this image is a fourdimensional image. As a result, we can apprehend Takahashi’s newest sculptures as four-dimensional images, and, namely, his attempt to yield spatiotemporal images. (Illustration 5)